Thermodynamic Legendre Transforms

Statistical mechanics is introduced as the unified theory explaining thermodynamics—but nobody taking it even understands thermo. Derivations in stat-mech tend to arrive at some formula for a Helmholtz Free Energy, or Gibbs, or one or another definition of the specific heat—but so what? These things are all too arbitrary and disconnected to compress easily into memory, and the derivations make use of innumerable seemingly-arbitrary partial derivatives; getting from one expression to any other amounts to navigating a labyrinth.

This was my experience, anyway, and none of my peers seemed to understand it any more than I did. Here, years later, are some resources to help make sense of things.

Table of Contents

- I. The Potentials

- II. Legendre Transforms

- III. Conventional Thermodynamics

- IV. Dimensionless Potentials

I. The Potentials

First, for reference, I’ll write out the mess of objects under discussion: a zoo of different “potential functions”, and their differentials. Each is given with its typical “Legendre Transform” relationship to the energy; more on this later. The examples are not meant to be meaningful as formulas, but they will at least serve to demonstrate the kinds of functional forms one tends to see for the properties we’re talking about here.

Starting with energy:

| Name | Arguments | Expression | Differential | Ideal Gas Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Energy |

Note that

Next we have three potentials which relate to the energy by “swapping” the entropy/temperature and pressure/volume variables:

| Name | Arguments | Expression | Differential | Ideal Gas Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Helmholtz Free Energy | with | |||

| Enthalpy | ||||

| Gibbs Free Energy |

Think of Helmholtz as the “something like the energy”, but specifically in a closed container where you can control the temperature and

Enthalpy I do not understand the point of at all.

We can additionally swap the

| Name | Arguments | Expression | Differential | Ideal Gas Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Landau Free Energy |

Landau Free Energy represents an “open” system which can exchange particles with its environment at a fixed chemical potential

So far we have been working with the three variables of a chemical fluid—

| Name | Arguments | Expression | Differential | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Magnetic) Internal Energy | ||||

| (Magnetic) Helmholtz Free Energy | ||||

| Magnetic Free Energy |

Here we started with a different expression for the energy

Finally, entropy itself:

| Name | Arguments | Expression | Differential | Ideal Gas Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entropy | or, though this uses a |

Entropy is related to the above potentials not via a Legendre transform but as the inverse of

Note that

II. Legendre Transforms

All of those definitions are a mess. Now to make sense of them.

What we are usually taught is that those expressions like

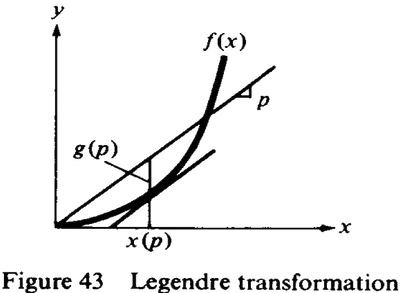

We will need the right sense of what a Legendre transform really is. Unfortunately, the way these are usually taught conveys no “sense” at all. Sometimes these derivations are accompanied by strange diagrams of tangent lines to a function

But this gives no insight at all. Why those lines? Why would anyone DO that?

I tried an article called “Making Sense Of the Legendre Transform”, but it came up short of making sense of things. It was a post on ForeXiv which finally offered, to me, a cogent explanation of the Legendre Transform for the first time.

The “transform” in question turns an

The right view is this. To take the Legendre transform of a convex function

- Take a derivative

- Invert the derivative

, - Integrate to give a new function

:

That is: all you do is invert the first derivative! One actually performs these operations so rarely that it’s easy to never learn how to do one! But apparently this is just a function inverse—of

That we’re “inverting the derivative” doesn’t completely determine the form of the Legendre transform. Ultimately the question of whether it’s right is whether it’s useful for explainig the physical world. But we can try to justify the particular choice to integrate to get

First,

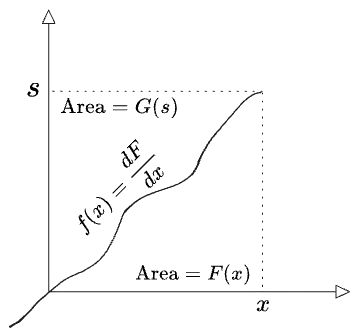

Second, there’s a nice graphical relationship between

Evidently

The inverse transform produces the original function by reparameterizing both regions by

This will often be written symmetrically, with the understanding that one parameterizes all terms by either

Apparently, there are three equivalent ways to calculate

- Integrate along

: - Integrate along

: - Or, plug in:

A few notes:

-

For convex functions, the transform “conserves” all of the information in the function, as can be seen in the diagram above. Thus if a function has multiple arguments like

, then taking its Legendre transform can be thought of as a reparameterization of one of its arguments in terms of the derivative w.r.t. that argument. It’s as if we had a blackbox with an inlet that says “takes s at a rate of ”, and we swapped it to now take s at a rate of .” It “wants” to be written like , but this steps on with our normal notation, as the new function almost certainly doesn’t have the same functional form as the original . -

We’re not thinking about the lower bounds of integration, but all three terms in the Legendre formula

are really integrals: It all works out as long as all three integrals are taken over the same region in

space, as can be seen graphically. -

We can also see this as “integration by parts”

, except from a perspective where the integrated function is the principle object of interest, rather than the integrand . In fact it may make the most sense to think of Legendre as a transform of differentials :

After all, Legendre transforms tend to arise when working with energies, whose absolute values are not meaningful. The differentials are perhaps the “true” relationships, while the integrated values are only meaningful relative to some reference frame; an energy floor, at least.

- Sometimes one sees an expression with a

or in it, which is needed when Legendre-transforming a non-convex function, projecting into the smaller space of convex functions. I’ll skip this for this post, as essentially all the functional forms of interest in thermoynamics are convex.

I find it helpful to characterize the “gesture” one takes in a Legendre transform. The basic gesture is “unwrap—invert—rewrap”: we differentiate to expose the derivative, flip the graph, then integrate again.

Because it’s just an inversion, it’s an involution on the space of only convex functions.

Because we discard information in the unwrap step (differentiation throws away constants), we would normally have a free parameter on the rewrap step (the lower bound of integration) but we have to choose this to readd the constant term discarded at the beginnning, such that the whole operation is an involution. This makes

Compare this to the “gesture” of a matrix inverse, which could be implemented as: rotate to a diagonal basis—invert—unrotate. This is also an involution on the space of invertible matrices, and here again one must unrotate into the original basis to reattain the information that was discarded, such that the combined operation is basis-independent.

Contrast with a Fourier transform, which is not an involution; instead the forward and inverse Fourier transforms have the senses of “rotate” and “unrotate”; they invert each other but they are not the same operation.

The two simplest examples of Legendre transforms, and also ones most commonly encountered, are those functions whose first derivatives are their own inverse functions:

Note the constant terms flips signs, and that a term not involving

III. Conventional Thermodynamics

Now we’ll tidy all of those thermodynamic functions. Some of this section is based on the “Making Sense of…” paper, but that paper doesn’t quite go far enough.

Note again that a Legendre transform operates on a single argument of a function at a time. Let’s look at what happens when you transform one argument followed by another. Let

Then we can either transform

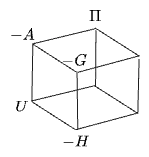

Clearly you get 2x2 different functions. And we see that you could transform many variables at once by

At this point an annoying bit of pedantry comes up which will help to clarify the situation in thermodynamics. The above diagram shows what you get if you view the final doubly-transformed function

Which is right? Well, both are: you can transform the function

This approach will supply a map for our thermodynamic potentials. The different combinations of Legendre transforms with respect to the three arguments of

The signs look rather arbitrary! The only explanation I can see for the minus signs on

If we instead were to take

That doesn’t tell us much, but it’s nice to know some sense exists to the pattern.

Next we have the face spanned by

The lower left function doesn’t appear in my stat-mech book, but could easily be defined.

In all they make a cube:

The signs indicate what you would get if you derived every potential via "

Finally we can write down a separate face you would use if you had magnetic energies:

IV. Dimensionless Potentials

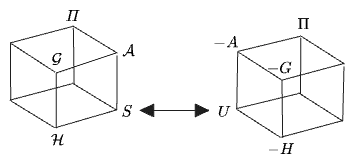

What about entropy

As detailed above, entropy is not a Legendre-transform of any of these potentials; instead it is obtained by inverting

We can therefore create a second cube of “transformed entropies” starting from

The “Making Sense Of…” paper suggests it would be more intuitive to use Legendre transforms which start from the entropy. They suggest a dimensionless entropy

We’re then free to introduce dimensionless analogs of all of the potentials (

These two “transformed entropies” are easy to relate to back to the normal “transformed energies” because

Mostly this approach is only useful to clarify the relationship of

And that’s it. I wish I’d had all of this back when I first made contact with stat-mech., so I hope it helps someone else.

References:

-

There doesn’t appear to be a great notation for “inverse of a function w.r.t. a single argument”—a glaring omission from mathematics, I think. See this Math Overflow post; the elementary example is the relationship between

, , and . The ForeXiv reference above uses Sussman’s notation which here would be . ↩

Comments

(via Bluesky)