Multiplying Vectors

Table of Contents

Vector Multiplication

Our definitions of multiplication or division by a scalar will carry over directly from the 1D case. We have, for some

But how should we define multiplication or division between two vectors?

In one dimension it was simple enough; for

The thing

This might work in 1D, but for higher dimensions We will want to be more thorough. We’ll start by asking: what properties should the multiplication of two vectors obey?

-

Multiplication ought to reduce to the obvious definitions in simple cases—otherwise it’s not really “multiplication”! The two “familiar” senses of multiplication of

are: - The length of a line consisting of

copies of , or copies of . - The area of a rectangle with sides

and

- The length of a line consisting of

-

The multiplication operation ought to play nicely with the “linear combinations” we used to define vectors in the first place. Multiplication of numbers distributes like

, and it seems sensible that a similar “distributive property” hold over combinations of vectors. If we call the undefined operation for the time being, we want: Taken together we will call these properties “linearity”.

-

The value we get for multiplication ought to depend on the exact vectors involved, and on the fact that they are vectors at all. We could just define multiplication to simply multiply the lengths of the vectors, like

, which obviously means something. But this doesn’t even care that they’re vectors; they could as well just be numbers. -

If possible, multiplication should be a purely geometric operation, defined in terms of the vectors themselves without reference to a choice of basis, and if possible, a choice of metric—although it seems likely that this second condition won’t be possible, since both simple cases in condition (1) make explicit reference to “length”.

Of all of these properties, the first is the most intuitive, so we’ll start there.

Linearity

We gave two “senses” of the multiplication of numbers: ”

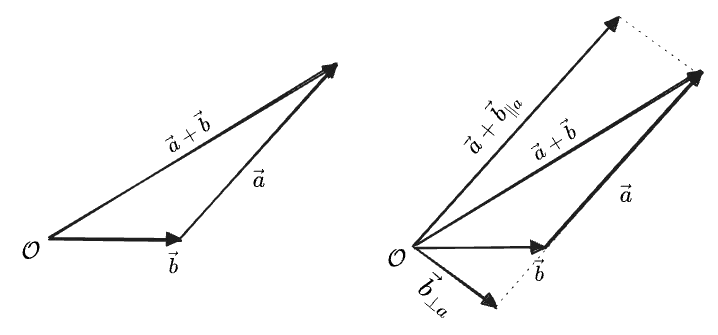

Let’s suppose instead that we have one multiplication operation which gives the prescribed results for parallel and perpendicular vectors, and now let us ask what “linearity” tell us about its value on any other pair of vectors. We’ll first illustrate how linearity works in practice with a simple graphical example:

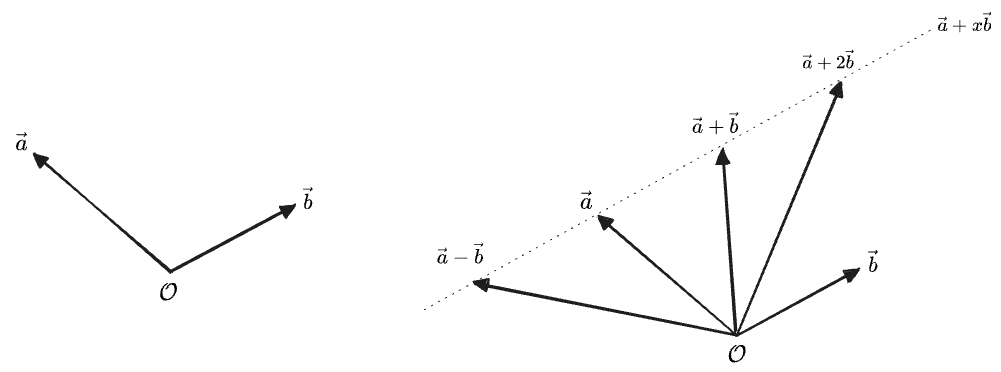

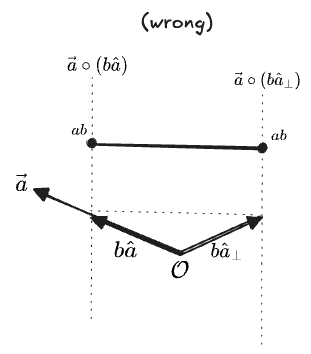

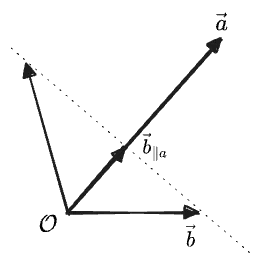

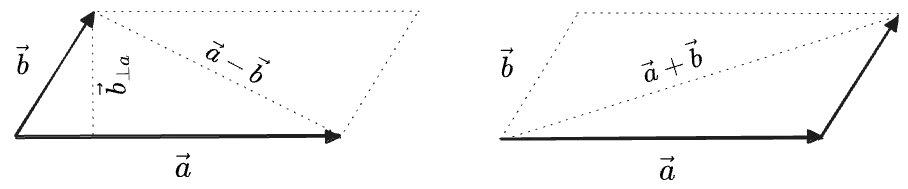

In the image above, we have chosen two vectors

For fixed

This should hold for any vector

And actually, this tell us more; it also means that

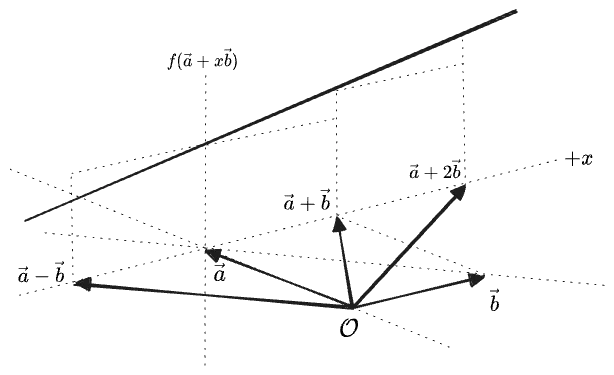

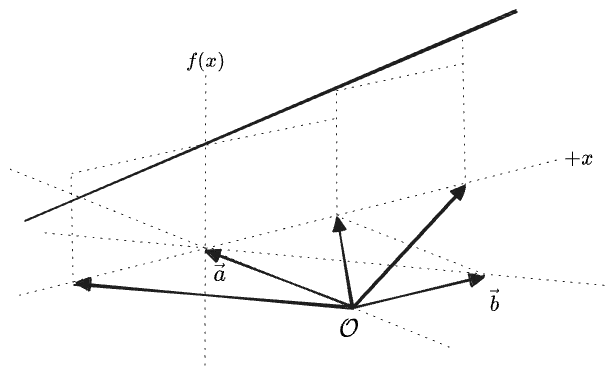

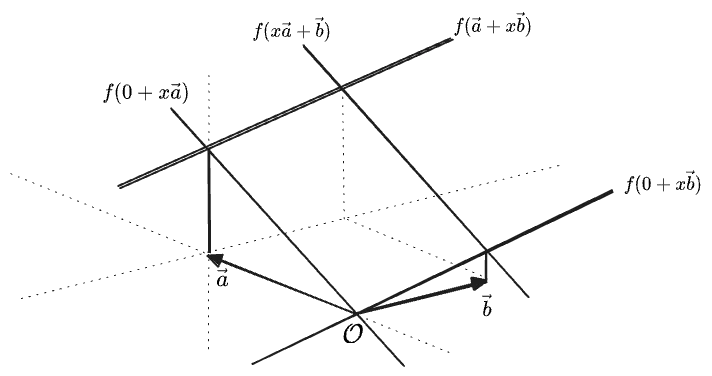

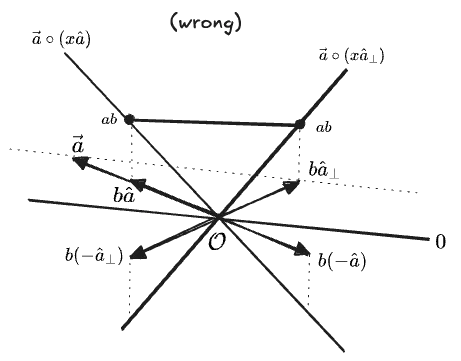

Linearity, then, is a very strong condition: the only thing a linear function on the 2D plane can do is “tilt” the plane, as can be seen in the above diagram. It can’t even have a “

Now, having established the geometric meaning of “linearity”, we can ask what it means for “multiplying two vectors” to be linear in each argument.

If we fix one vector

If we linearly interpolate between those exact two vectors, then the value of

But the only way for this to be linear is if the value does not vary along the line at all. Then we immediately know the value everywhere else, because

… well, apparently this is a function we could define. But it doesn’t look like a particularly useful one—except for the values

Let’s step back. Maybe those two conditions on the products of parallel and perpendicular vectors don’t need to be cases of the same operation. We can instead define two multiplication operations, each in terms of projections:

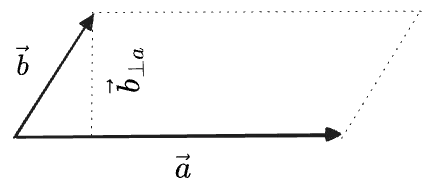

- One which multiplies the parallel components of vectors,

, which we will write as and read as a “dot product”. This is a natural generalization of the multiplication of two one-dimensional vectors; we simply ignore the rest of the space! - One which multiplies the perpendicular components of vectors,

which we will write as , read as “cross product”. This is the natural generalization of the sense of multiplication producing an “area”.

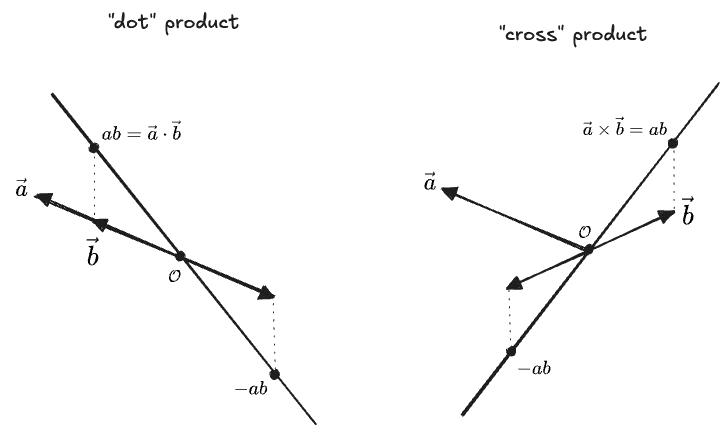

Visualizing these as linear functions of the

Multiplication 1: The Dot Product

The “dot” product needs to multiply the lengths of vectors that are parallel. The simplest way to define an operation

What about the opposite projection,

So we ought to think of this product as a “symmetric projection”—it is a projection which incorporates both lengths, and doesn’t care which one you projected onto the other or the order of the two arguments. In all we have a few names:

- “dot product”

- “symmetric multiplication”

- “symmetric projection”

- or a “scalar product”, because it produces a scalar, although in two dimensions

will also give a scalar, so this won’t be very helpful. - “inner product”

If we don’t want to use

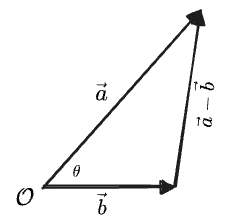

We do some geometry: first, draw

We’re going to compose

Then we can write a Pythagorean theorem relating the three:

Then at the same time we can expand in our standard basis of

Comparing the two, we see the following equivalence

The argument was completely symmetric between

Because we didn’t specify what that basis was, it must hold in any basis.

We can do a lot with this. For one, we can write the squared-length of any vector as the dot with itself:

We discussed a lot of caveats about the definition of “length” above—have we now found “innate length” of a vector? No—the dot product depends on the choice of metric, since it is composed of vector lengths, and in fact the expression would be more complicated if our basis vectors were not unit-length.

In fact, our derivation provided an expression for the dot product

This is one form of what is called the “polarization identity”.

We can also use the dot product to write the “projection” in a way that’s easier to calculate:

As a “symmetric projection” the dot product must give zero for perpendicular vectors. Therefore

Graphically, this says that all of these

Finally, we can use the other projection definition

Multiplication 2: The Cross Product

Now, what about our other definition of multiplication, generalizing the “area of a rectangle”? Clearly the analogous multiplication formula is:

To find this in components this, let’s write

We get a result with a

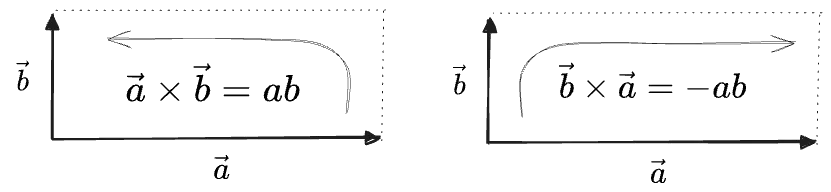

Well, our original “linearity” condition actually required that some areas come out negative; otherwise we couldn’t have linearity hold for two vectors adding to zero:

But the coordinate expression also tells us that flipping the arguments must the sign. So we get:

The second line holds because we have defined the

So these are “signed” or “oriented” areas; the sign depends on the order you choose the vectors around the rectangle:

You can always take an absolute value if you need the literal area.

I’ll write these as:

The

We have been casually using

which is a

This definition also implies that we can write a cross product as a dot product with

Note that these definitions only apply in 2D. In higher dimensions

Now, we found this definition by looking for a multiplication which gives the area of the rectangle formed by perpendicular vectors. What does it do on non-perpendicular vectors? If two vectors are parallel, antisymmetry requires that:

So parallel vectors have a cross product of zero.

What about vectors at some angle to each other? The value of

In the above the left triangle could be moved to the right. So we have:

Note that adding any component of

Drawing a diagonal in either direction divides the parallelogram into two triangles

Each has half the area of the whole parallelogram, which gives us a vector formula for the area of a triangle:

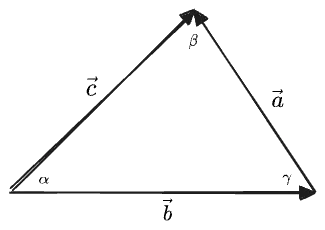

If we write

If we the angle between

We even get the right sign from

If we draw the triangle formed by

we can write three equivalent expressions for the unsigned area, in terms of each pair of sides, which leads to the Law of Sines:

The Shoelace Formula

Now we’ll demonstrate the usefulness of “negative areas”.

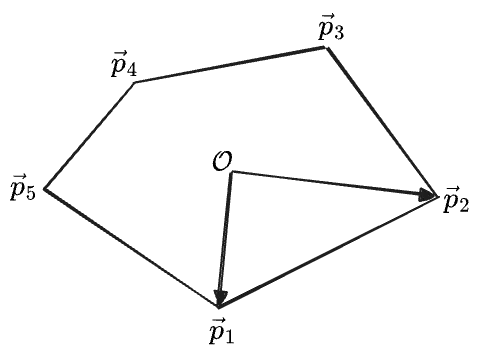

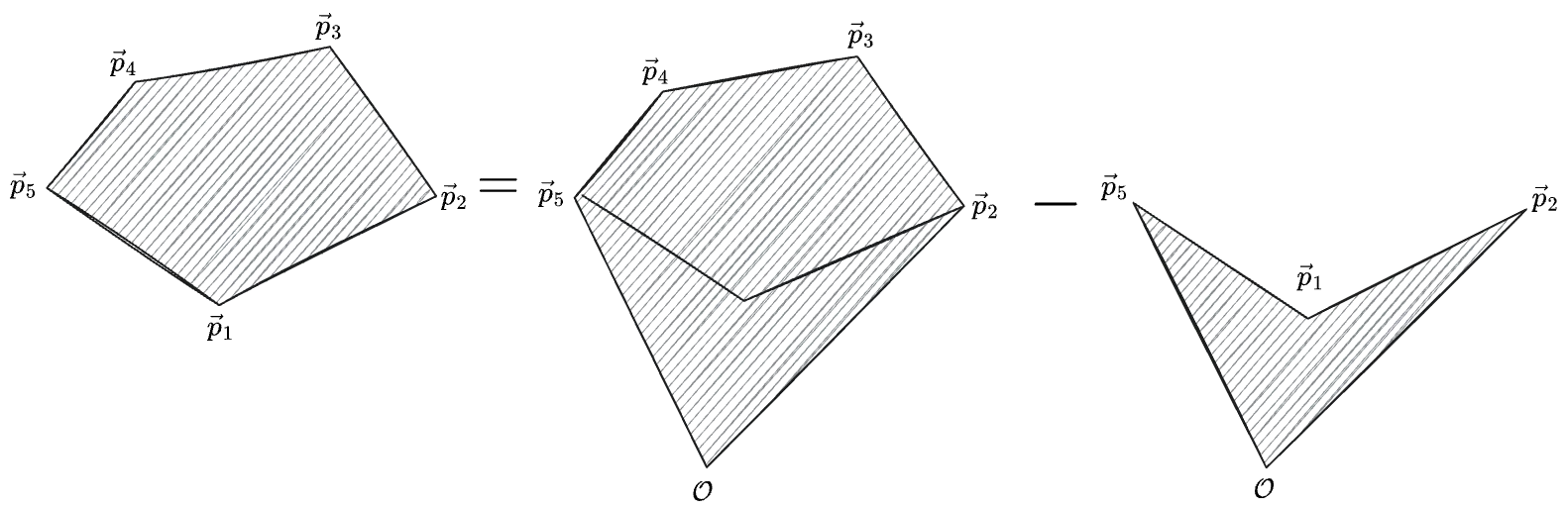

But this means that we can find the area of any polygon if we know the coordinates of all its vertices—we just carve it into triangles:

With

(The sum is periodic, so

The area of each triangle is equal to half the cross product of its two sides. We can use either the two sides formed by one vertex and the next (akin to taking

These formulas are equivalent because

This is called the Shoelace Formula for the area of a polygon, for reasons you can read on the wiki. It’s simple! It could be taught in high school! 2

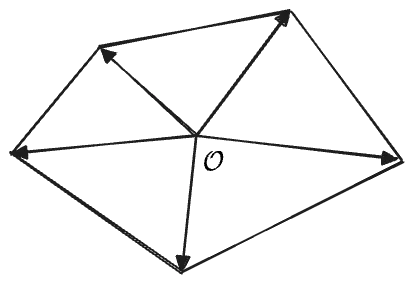

Remarkably, this still works if the origin is outside of the polygon—the oriented areas become negative for the part outside of the polygon, in exactly the way that cancels out all the overlapping contributions:

The corresonding sum is:

with the sign in the second term becoming negative because the original vertices were in a clockwise (negatively-oriented) order; this becomes a minus sign out front in the second line where I’ve rewritten them in counterclockwise order.

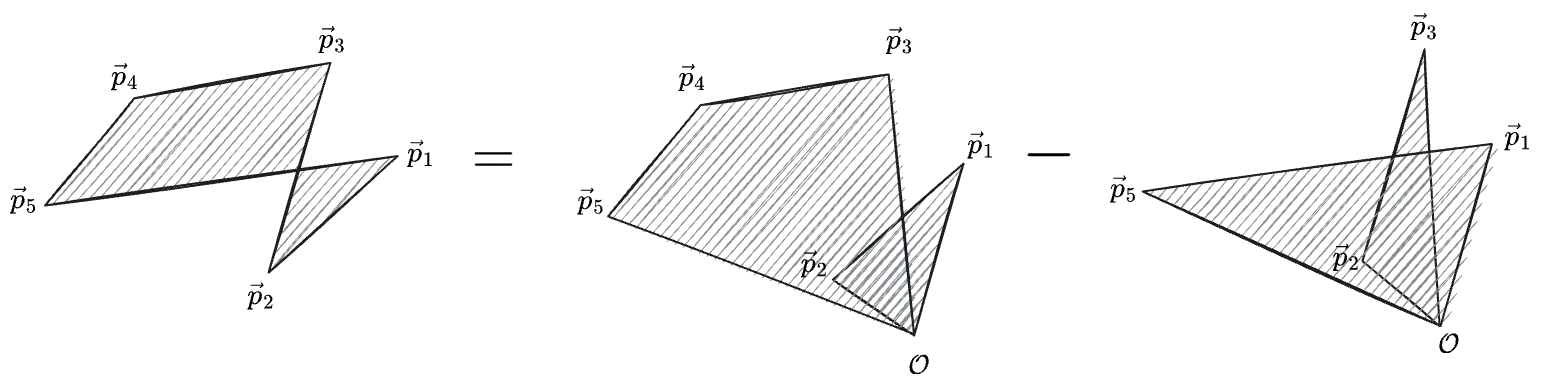

And it works even if the polygon’s vertices loop back on themselves, as long as we cancel out all of the negatively-oriented areas correctly:

The above stands for the sum:

This one’s harder to see, but if you stack all of those pieces of the sum on top of each other everything will cancel exactly to give the area of the l.h.s. polygon.

Multiplication 3: The Geometric Product

To recap: we asked that our multiplication operation on vectors have four properties:

- intuitiveness, and in fact we found we needed two products to match both senses of intuition for parallel and perpendicular vectors

- linearity, which is manifest in the definitions

and . - that they were purely “geometric” concepts, independent of a coordinate system. This we have satisfied by defining both operations in terms of projection vectors, though the values of the multiplications do still depend on “length” through the length of the projections.

- that they depend on the unique vectors. We somewhat satisfied this; each multiplication has some vectors it considers equivalent (like sliding the parallelogram) but otherwise does depend on its inputs.

We made use of the purely-geometric concepts of projection/rejection in defining the two products, so we should expect they will be well-formed. But let’s also check: what do these results do if we rotate the whole coordinate system? If we express both of our input vectors in terms of the “angle with respect to the

Then we can write

We get two trig identities, each depending on the difference of the angles—which means they will be rotational invariants:

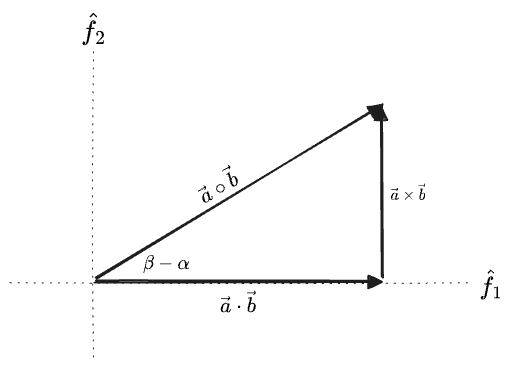

This also suggests we can create write a Pythagorean theorem with the two products:

This is called Lagrange’s Identity. Lagrange’s Identity lets us write a sort of “polarization identity” for

So both products can be derived from only the definition of length. But the cross product involves a square root and therefore a

Interestingly, Lagrange’s Identity suggests we might think of the two products as two components of a vector in a new vector space—something we didn’t even consider at the outset of this “multiplication” section. Calling its basis

The geometric product maps two vectors (here in

The geometric product IS linear in both arguments. Recall that our “linearity” argument did not allow us to define a single product which produced a scalar and satisfied both intuitive definitions of “multiplication”. Rather than choose one or the other as we did for the dot and cross, here we’ve simply chosen both.

Unlike the dot and cross products, the geometric product has no particular symmetry w.r.t. a swap of the two input vectors: its first term is symmetric while the second is antisymmetric.

How should we interpret this “geometric product”? When the two vectors are parallel it has only the first component; when they are perpendicular it has only the second. It is proportional to the lengths of both vectors. And we know it is invariant with respect to rotations of the original space

So it would appear to be some kind of characterization of the relationship between the two vectors: perhaps it tells us how to transform one into the other? This will bear out, but we don’t have enough machinery to go any further at this point.

More Products

You could write two more products which look like

These two products are not rotationally invariant; instead they rotate at double the rate of the coordinate system. But they do obey Lagrange’s identity:

These in fact correspond to the real and complex parts in the multiplication of complex numbers:

The angle-addition behavior implies that multiplication according to these products acts like “composing rotations”, relative to the fixed axis we measured

We can also write a “fully general product” which simply distributes over all the basis vectors, the “tensor product”:

In the tensor product we don’t even try to combine any of the terms into scalars; we leave them all distributed out, and we consider the basis elements like

It is not obvious from the expression, but the tensor product does not depend on the choice of basis:

We won’t do much with this thing. But it’s worth remarking that our other products amount to particular ways of “mapping” the general tensor product to smaller spaces.

The dot product amounts to choosing

The two “opposite-sign” products just mentioned make the opposite choices.

-

What we’re describing here is a

which is a “linear in its argument ”. This is not really the same as a “linear function of an argument ”, like a 1D line ; a function “linear in an argument” must have . ↩ -

I distantly recall expecting to learn how to calculate polygon areas in high school. But we never did, all because high school math is afraid of vectors. In fact they’re a completely natural object to consider after some basic geometry and algebra. I think the kinds of things I’m demonstrating in this post would make a good Algebra II curriculum, and would feel far less arbitrary than what is normally considered at that point in one’s education: conic sections? Roots of polynomials? Who cares? ↩

Comments

(via Bluesky)